The Women’s Professional Rodeo Association is the oldest women’s professional sports organization in the world, and in the last seven decades has made an immeasurable difference in the lives of those who live the Western way of life.

Originally published in the September 2023 issue of Team Roping Journal.

It’s a rich environment for women in rodeo these days. More women right now are entering—and winning—jackpots and rodeos than ever in history. Team ropers Beverly Robbins heads better and Whitney DeSalvo heels better than a lot of men. They can hold their own, anywhere.

But there’s just something about an even playing field. Something about backing into a box knowing that a big win means you’re the best of your gender, a true GOAT. For 75 years now, the greatest female team ropers in the world have been able to come tight on those big-time bragging rights.

This organization was created by women, for women, and it’s very important that it exists so our events can continue to be only for women.

Jimmie Munroe, WPRA President

READ MORE: The First Family of Futurities, Remembering the Impact of Family Patriarch Dale Youree

Trailblazers

This is the milestone anniversary of the Girls’ Rodeo Association—now the Women’s Professional Rodeo Association (WPRA)—because a few dozen trailblazers (including eventual team roping world champion Betty Dusek) came together in 1948 to change the scope of women’s competition in professional rodeo.

“We were tired of not getting our due and didn’t have formal rules,” Dusek said. “We were ready for some organization, honestly, just to make everything better.”

The first team roping director—eventual three-time world team roping champ Blanche Altizer Smith—was just 19 years old in ’48, and Dusek was 18. Decades later, Smith’s nephew, Mack Altizer, was ahead of his time by adding women’s breakaway roping to his PRCA rodeos in west Texas. GOATs like Lari Dee Guy entered those rodeos.

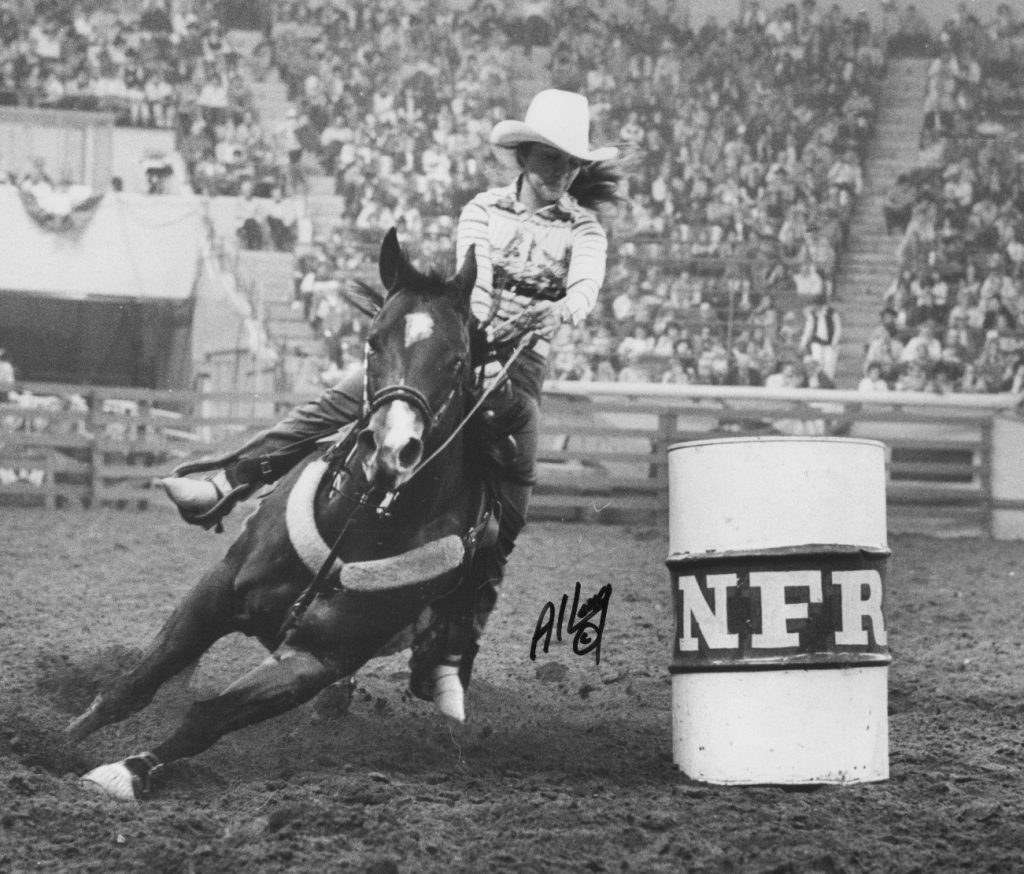

Now a Hall-of-Famer, Guy and her protégé Jackie Crawford became two of the best female team ropers of all time—at both ends. That gauge was possible only because they were able to team rope at the WPRA World Finals, which for years was called the Women’s NFR. Their multiple world championships lent legitimacy and celebrity to the rise of breakaway in the PRCA ranks and made them household names in that televised event.

The group’s mission was to give women legitimate opportunities to compete, as well as establish an alliance with the PRCA (then RCA) to host women’s events in conjunction with its rodeos. They drafted rules, enacted a point standings system to crown world champs, and got to work persuading committees and producers to hold women’s contests according to GRA rules.

But a decade earlier, nobody watched Guy win back-to-back WPRA world championships heeling in 2010 and 2011 and four more gold buckles in the heading over the next nine years (nobody’s ever done that). Nor do many people remember the Driggers-and-Nogueira-like rampage that J.J. Hampton and the late Melissa Brillhart went on, winning the world team roping title in four straight years from 1996-1999, with Brillhart capturing one more for five total. And that was in the days they earned it, via all-night drives and early-morning slacks.

But members knew. Young cowgirls have always known “WPRA” as another word for “elite.” And while barrel racers heretofore got the media limelight, many of them also roped or competed in the WPRA’s steer-wrestling-like event. (Steer undecorating was offered from 1970–1988.)

For instance, perennial NFR contender Dona Kay Rule made the Women’s NFR in heading in 2002, and former NFR barrel racers Shelly Murphy and Nancy Hunter were the WPRA’s Montana Circuit and Turquoise Circuit heeling champions in 2012 and 2016, respectively. Beverly Robbins, who placed in the short round of the Bob Feist Invitational; Willow Wilson, the only female to make the short round in team roping at the PRCA’s Cheyenne Frontier Days; and Cadee Tew, who made the PRCA’s Montana Circuit Finals Rodeo recently in team roping; first were circuit champions in the WPRA ranks and pursued world titles.

READ MORE: Martha Josey: A Fashion and Barrel Racing Icon

First to organize

The WPRA is the oldest women’s sports league in the country. But cowgirls weren’t the only athletes jostling for a seat at the professional sports table. In 1950, just over a dozen women launched the Ladies PGA. About 20 years later, as the CEO of Colgate led the way in making corporate America take a serious look at women’s pro golf, nine other female athletes took a stand on the tennis courts. Distraught with the growing disparity in prize money and playing opportunities for women in professional tennis, they risked suspension to form the Women’s Tennis Association in 1970.

Read More: A Conversation with Legendary 11x World Champion Barrel Racer Charmayne James

Those ladies worked tirelessly to cultivate relationships with promoters and sponsors and market their league, with the end goal of equal prize money. That was also Pam Minick’s first duty as a WPRA board member 45 years ago: publicity. It was a time when the WPRA was struggling to get their event included at pro rodeos, despite barrel racing being favored by fans. In fact, challenging the status quo in the 1980s and ’90s was a delicate dance of retaining the original lure of cowgirls—beauty—while pushing for equal money.

“Appearance and participation and crowd approval, those were our main selling points,” recalled Minick, a former Miss Rodeo America and roping world champion who smiles at the thought today of requiring cowgirl contestants to carry flags in grand entries and wear color—no blue jeans were allowed.

At the same time, the WPRA made the decision in 1981 not to approve any PRCA rodeo that wouldn’t offer the women at least half the purse of the lowest-paid men’s event.

“That was a tough one and we lost some rodeos,” said Minick, who served as vice president for 16 years. “Big rodeos. Like Houston. But we had to start somewhere. It was Nestea and Purina who stepped up with dollars to bring our event up to 50% of the added money of the men’s.”

Barrel racing was chosen by the men as the lone women’s event, but it never stopped the WPRA from providing a showcase for ropers. After all, Jimmie Munroe, the WPRA president for 22 years and counting of the past 45, was an 11-time NFR barrel racer who, in 1975, remarkably won both a barrel racing world championship at the NFR and a WPRA tie-down roping world championship. She never let women’s roping take a backseat to barrel racing.

“Those founding women in 1948, they represented several different events, all of which were important to them,” said Munroe, who’s enshrined in multiple rodeo Halls of Fame. “That’s the history of this association. I think it’s very important to keep that part of our history alive.”

It’s indeed alive. Nellie Miller became the first woman to win the all-around at the PRCA’s Red Bluff Round-Up in 2019 and Ari-Anna Flynn did the same thing in 2021 at the PRCA rodeo in Stephenville, Texas—the “Cowboy Capital of the World.”

LISTEN: The Future of Women in Rodeo ft. Jimmie Munroe, Sherry Cervi and Jackie Crawford on The Money Barrel

By women, for women

Running a nonprofit and juggling the opinions of thousands of strong-willed cowgirls takes a special leader. Those who’ve excelled over the years have also been hauling down the road; they’ve been winners.

Florence Youree served as president four years in the early 1960s, and Mildred Farris the following seven years. The two Hall-of-Fame legends were instrumental in getting a women’s event included at the NFR. Since then, much of the WPRA’s longevity is thanks to Munroe, who took the reins as president for the first time in 1978 and served through 1993. She led the way in women finally being paid equally at rodeos in the mid-1980s, with the sweet reward of Charmayne James sporting the No. 1 back number into the 1987 NFR.

Another Texas native who married a Montana cowboy, Carolynn Vietor, took over in 1996 and spent seven years seeing the WPRA through defining moments, including one at the NFR.

“They weren’t paying our women equally or paying both sides of the team roping,” Vietor recalled. “I was in a boardroom before a performance of the 1998 NFR, and the contestants threatened not to compete that night at all. I still remember Lew Cryer came in and said, ‘I’ve got to talk to you right now.’ And that was the night they—and us—got equal money.”

The NFR had been around 40 years when that milestone was reached. Along the way, Munroe and Vietor helped guide the WPRA after it won a lawsuit brought by a man trying to become a member, and after it won another when the Troy Ellerman-led PRCA decided to sanction its own women’s event.

“This organization was created by women, for women, and it’s very important that it exists so our events can continue to be only for women,” said Munroe, who noted that a birth certificate has always been required with application for WPRA membership. “It would be hard to keep men out of our events if we didn’t have a separate organization. During that litigation, we had producers like Shawn Davis testify that the reason they included our event was because it was all-female.”

A group of cowgirls, after all, is still a novelty—a delight for crowds. But there have been speed bumps. When the WPRA struggled, Munroe stepped back, both in 2011–12 and a decade later. Vietor did the same in 2013–15. In fact, women’s pro roping tomorrow depends on young women to run for director of their circuit, said Munroe, who was just 25 during her first year as president. And Minick would love to see the board of directors continue to be made up of not just “good hands,” but also good leaders.

“Over the years, these women were willing to give clinics and provide instruction,” she said. “That’s really the future of the WPRA, I think, for people to continue to hold the door open for the next girl to come through.”

A servant’s heart

Minick credits the WPRA’s longevity to directors who put aside their personal agenda for the greater good, who have “a servant’s heart” and who have truly carried women’s rodeo on their shoulders. Like Munroe.

“In the 1980s, every PRCA rodeo signed their contract during the NFR or at Denver, and when they walked in the room, Jimmie remembered all their names and commented on their individual rodeos, and had such a rapport with them,” recalled Minick. “I feel like the biggest money winners in women’s rodeo right now, Jordon Briggs and Hailey Kinsel, owe a debt of gratitude to her.”

Except, the biggest money winners in women’s rodeo at press time were not barrel racers They were breakaway ropers Hali Williams and Shelby Boisjoli, who, together, had banked $183,844 to Jordon Briggs’ and Hailey Kinsel’s $172,994 in early July. Thus, while it took 40 years for barrel racers to make decent money in ProRodeo, breakaway ropers have done it in five—in the regular season, that is.

Last year in all-girl team roping, 2022 WPRA World Champion Header Hope Thompson earned $21,671, while Lorraine Moreno strapped on the heeling gold buckle with $17,994.

But the WPRA’s persistence has paved a path that’s widening now for team ropers. Bob Feist Invitational producers have featured a lucrative All-Girl team roping for nearly 20 years, paying defending champs Kenzie Kelton and Whitney DeSalvo $20,000 in March. Plus, the WCRA paid Martha Angelone and Jackie Crawford $60,000 for winning an all-girl team roping in May.

The WPRA started with 74 members, 60 events and a payout of $29,000. Now, 75 years later, it has more than 3,000 members, some 1,500 events and payouts totaling more than $5 million—including the sanctioning of breakaway at a record 400-plus PRCA rodeos this season.

“I’m proud of the success of the WPRA,” Dusek said. “I always wanted to see more ropings, and I sure see a lot of them that pay darn good for the girls. I think it just keeps getting better.”

Today’s women are reaping the benefits of the sacrifices made by the world’s toughest cowgirls for the past seven decades. Nobody sums up their mission better than legendary tennis player Billie Jean King, one of the original nine women who launched the WTA and were recently inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame.

“There were three things we wanted for future generations,” King said. “First, that women would have a place to compete. Second, that they would be recognized for their accomplishments and not just their looks. Finally, that they could make a living playing their sport. Today’s girls are living our dream.”