When a barrel horse has a suspected airway issue, the first diagnostic tool that a veterinarian reaches for is the endoscope. This long, flexible tube equipped with a light and a camera allows clinicians to see within the horse’s upper airway while standing or at rest. This traditional standing/resting endoscopy is great for observing the condition of various structures and tissues within a horse’s airway, but it’s limited as far as how those organs function under exercise. Dynamic endoscopy helps remedy this limitation.

“It’s great for the glaringly obvious,” said Canaan Whitfield-Cargile, DVM, a surgeon and associate professor at the University of Georgia’s College of Veterinary Medicine in Athens. “It’s great for diseases that are present no matter what the horse is doing, like a mass in the throat or an infectious process.”

“Very small changes in the function of the throat can have a dramatic effect. Structurally it looks fine with an endoscope, but it’s the function that matters in performance horses. In order to determine if function is normal, we need to see what’s going on while the horse is doing its job.”

Canaan Whitfield-Cargile, DVM

What it cannot tell clinicians is how airway structures, specifically within the throat—the pharynx and larynx—function during exercise.

“When it comes to performance horses,” said Whitfield, “very small changes in the function of the throat can have a dramatic effect. Structurally it looks fine with an endoscope, but it’s the function that matters in performance horses. In order to determine if function is normal, we need to see what’s going on while the horse is doing its job.”

The next step in diagnostics is the dynamic endoscope, which is a shortened version of a traditional scope that’s outfitted to be used while the horse is moving—galloping on the flat, going over jumps and even racing around barrels. Video images are either stored for viewing at a later time or transmitted wirelessly to veterinarians allowing them to observe how structures within the horse’s throat function in real-time as the horse is working.

Negative Pressures

“Horses are incredible athletes,” said Whitfield. “They can move massive amounts of air because of their lung field—the size and volume of the lung relative to the size of the animal.”

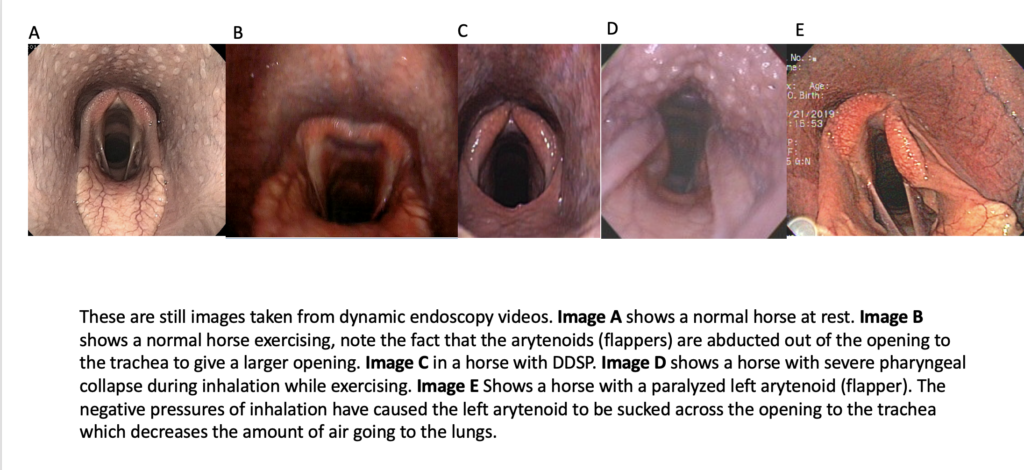

As a horse inhales, it pulls air through the relatively narrow upper airway, from the nose through the pharynx and larynx in the throat, and down the trachea into the lungs.

“The inhalation process produces a lot of negative pressure like a vacuum,” Whitfield explained. “If any bit of the horse’s upper airway isn’t stable for any number of reasons, it gets sucked into the air flow and reduces the diameter of that pipe. The air can’t get to the lungs because of this collapse due to the negative pressure.”

The instability and collapse often occurs in the horse’s throat at the pharynx and larynx.

“It’s only there during the negative pressures of breathing,” he added. “With dynamic endoscopy, it allows us to recreate that negative pressure because the horse is doing its job. When the horse is standing in the stocks, it doesn’t have to inhale hardly at all because it has such an amazing capacity to breathe.”

Performance Positioning

What dynamic endoscopy can tell you is influenced by what the horse is asked to do, said Whitfield.

“You can have a horse that’s perfectly normal galloping around the pasture or on the longe line, but as soon as you tack them up and start using them the way they’re supposed to be used, everything changes,” he noted.

If a horse is having trouble making a barrel run but is only observed while loping around the arena, the dynamic scope might not give clinicians the same information as making a run.

“Head and neck position matters hugely for breathing,” said Whitfield. “If you take your chin and tuck it to your chest, you can feel the pressure in your throat.”

The same is true for horses.

“When the horse is free longeing, they can stretch their neck and nose out, making a nice straight line between the tip of its nose and its lungs, which makes breathing a lot easier,” he said. “Yet almost no performance is done with the horse’s head straight out. When ridden, how their head and neck is flexed depending on the job can absolutely affect how the horse’s airway functions.”

Dynamic Difference

While some upper airway diseases can be diagnosed while the horse is at rest, it’s not the case with all of them.

“There are diseases that you have zero ability to diagnose unless you’re doing dynamic endoscopy,” said Whitfield. “One of those is pharyngeal collapse. The pharynx is the soft tissue in front of the larynx. At rest, that’s never going to collapse. It can only be diagnosed when the horse has its head and neck in performance position while recreating the negative pressure.”

Even upper airway diseases clinicians observe with resting endoscopy can be very different when the horse is exercising, said Whitfield. One of those conditions is laryngeal hemiplegia, commonly known as paralyzed flappers.

In the larynx, the arytenoid cartilages, commonly referred to as the “flappers,” and the epiglottis close off the trachea when the horse swallows to prevent food and water from entering the lungs. The flappers cover the trachea on the left and right, like swinging doors. Although both flappers can be affected with a condition called laryngeal hemiplegia, it’s typically the left that becomes weak or “lazy” and sometimes permanently paralyzed.

“When you scope a horse at rest, you will see tons of horses with some degree of laryngeal hemiplegia,” said Whitfield, “but you don’t know how it affects the horse until you look at it dynamically.”

The degree of paralysis of a flapper is graded as 1 for normal, 2 to 3 being weak or lazy and 4 completely paralyzed. The dynamic scope can tell if the grade of severity is likely to be causing problems and require an expensive surgery, or if it’s more of a nuisance.

“A horse at rest may be a grade 2,” Whitfield explains, “yet when the horse performs, changes his head and neck position at work, it becomes a grade 4. Typically, a grade 2 is something you wouldn’t do anything about, but a 2 that turns into a grade 3 or 4 during performance may need surgical intervention to be able to do its job.”

The opposite scenario has also been seen on dynamic scope, said Whitfield.

“You’ll also see horses that are grade 4 at rest, but when you exercise the horse, it functions just fine,” he said. “Certainly, that scenario is much less likely, but it does happen. Surgery is expensive enough that you don’t want to have it done if the horse doesn’t need it.”

Another common condition that’s often visible with resting endoscopy is Dorsal Displacement of the Soft Palate (DDSP). However, how badly it affects the horse is usually determined by dynamic endoscopy.

| READ A Tough Climate Makes for Tough Competitors

What About Bleeders?

While the dynamic scope isn’t long enough to see down into the lungs while a horse performs, any obstruction it finds may have a correlation to Exercise Induced Pulmonary Hemorrhage (EIPH), the rupture of blood vessels within the lungs that’s commonly referred to as “bleeding.”

“Not every horse that bleeds is going to have a dynamic obstruction, and not every horse with a dynamic obstruction is going to bleed,” said Whitfield, “but there is a correlation between the two.”

If an obstruction increases the negative pressures within the lung, it can be enough to cause the small blood vessels to rupture, he noted.

“I think many horses with EIPH should undergo dynamic endoscopy at some point to make sure there’s no upper airway component that maybe exacerbating the EIPH,” he added.

Limitations

Whitfield said one of the challenges for dynamic endoscopy is the lack of detail and limited depth when compared to a standing scope.

“Dynamic endoscopy should always be combined with resting endoscopy,” he said. “With resting endoscopy, you can see a lot more detail of the horse’s airway. You can go down the trachea a little bit, you can go in the guttural pouches. You cannot do those things with dynamic endoscopy, so a combination of resting and dynamic endoscopy can provide you with the best information.”

Another limiting factor is recreating the right conditions.

“While we can do them at a race, it’s easier at the veterinary clinic,” he said. “At the clinic, we’re not recreating all the variables of a competition setting—the anxiety or the dusty environment. I believe there’s a different function in the upper airway in dusty environments.”

The findings under a true performance setting might be more severe than the findings observed in a clinic setting.

“When you do dynamic endoscopy at a vet clinic, the changes you see might not be as severe as what you would see in a real performance setting—one that we can’t recreate,” he warned.

“We often see issues in the upper airway when the owner wasn’t necessarily thinking that was the cause. So many horses get injected due to poor performance, but no one thinks to check the other body systems that could be involved. The upper airway is one of those systems that’s often overlooked.”

Canaan Whitfield-Cargile, DVM

Don’t Forget the Upper Airway

When it comes to poor performance, Whitfield advises clinicians to consider the upper airway.

“The number of reasons a horse can’t meet its performance expectations are huge,” he said. “It could be lameness, a skeletal issue, a heart issue, an upper or lower airway issue. We often see issues in the upper airway when the owner wasn’t necessarily thinking that was the cause. So many horses get injected due to poor performance, but no one thinks to check the other body systems that could be involved. The upper airway is one of those systems that’s often overlooked.”

The use of traditional and dynamic endoscopy is the best way to rule out possible performance-limiting upper airway issues.

Meet The Expert: Canaan Whitfield-Cargile, DVM, PhD, recently returned to his alma mater—the University of Georgia’s College of Veterinary Medicine in Athens. He is a former associate professor at Texas A&M University’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences in College Station, Texas. A South Carolina native, Whitfield did his undergraduate work at Clemson University before obtaining his veterinary degree from the University of Georgia. He completed his surgical residency at Texas A&M. Whitfield practiced privately for three years before returning to College Station to complete a PhD in biomedical sciences. Whitfield is a board-certified specialist in surgery as well as sports medicine and rehabilitation. His special interests include equine soft tissue surgery, specifically of the airway and gastrointestinal tract. He also has research interests in comparative gastroenterology between horses and humans.